A 3200 year-old #Egyptian tablet shows, they took attendance at work and recorded absences and the reasons range from embalming relatives to brewing beer...

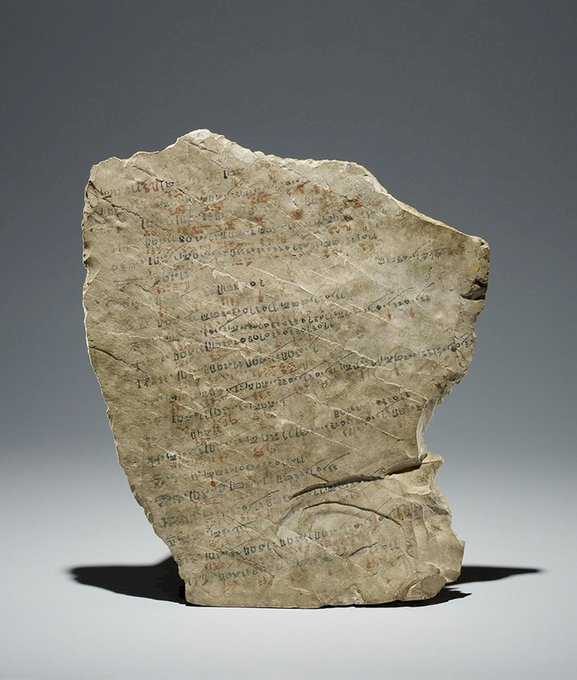

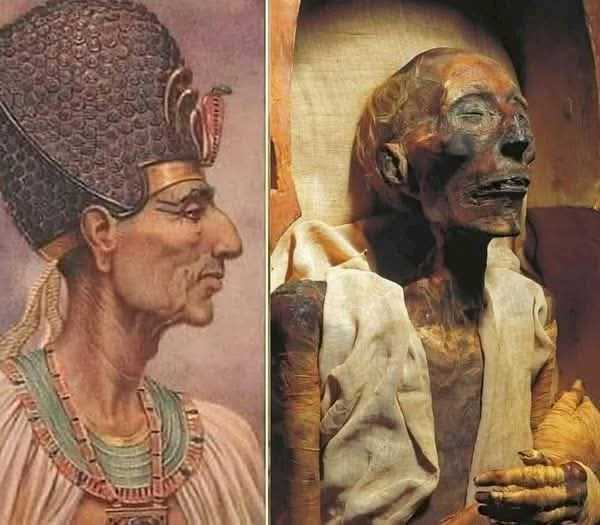

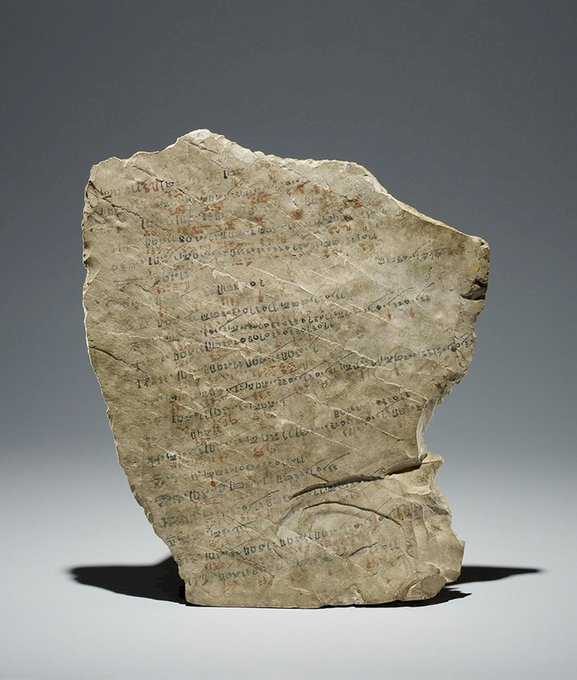

In a remarkable intersection of history and modernity, an ancient limestone tablet, dating back 3200 years, offers us a mesmerizing portal into the heartbeat of human existence—a connection between eras that spans millennia. At the core of this aged relic lies a revelation that transcends time: art of absence management is a practice deeply etched into the annals of human society. This historical artifact, affectionately referred to as an ostracon, bestows upon us a unique glimpse into the labor-management practices of ancient Egypt, unfolding during the illustrious reign of Ramses II, around 1250 BC.

As we embark on a journey through the corridors of time, deciphering the meticulously inscribed hieratic script on this aged tablet, we unearth not merely the labor patterns of a bygone era, but rather, an intricately woven tapestry of existence that mirrors the intricacies of modern-day work-life balance.

Calling in sick to work is apparently an ancient tradition. Whether its the sniffles or a scorpion bite, somedays you just can't make it. As it turns out, Ancient Egyptian employers kept track of employee days off in registers written on tablets. A tablet held by British Museum is an incredible window into ancient work-life balance. The 40 employees listed are marked for each day they missed, with reasons ranging from illness to family obligations.

The tablet, known as an ostracon, is made of limestone with New #Egyptian hieratic script inked in red and black. The days are marked by season and number, such as “month 4 of Winter, day 24.” On that date, a worker named Pennub missed work because his mother was ill. Other employees were absent due to their own illnesses. One Huynefer was frequently “suffering with his eye.” Seba, meanwhile, was bit by a scorpion. Several employees also had to take time off to embalm and wrap their deceased relatives.

Some reasons may seem strange to modern ears. “Brewing beer” is a common excuse. Beer was a daily fortifying drink in #Egypt and was even associated with gods such as Hathor. As such, brewing beer was a very important activity. Fetching stones or helping the scribe also took time in the workers' lives. Another reason is “wife or daughter bleeding.” This is a reference to menstruation. Clearly men were needed on the home front to pick up some slack during this time. While one's wife menstruating is not an excuse one hears nowadays, certainly the ancients seem to have had a similar work-life juggling act to perform.

Imagine standing amidst the sun-drenched landscapes of ancient Thebes, a city that once thrived along the fertile banks of the Nile, its heartbeat echoing through the bustling community of Deir el-Medina. Here, within the very heart of this historical tapestry, lies an artifact of profound significance, an ostracon, etched with ink and time, its surface bearing witness to the daily rhythms of labor and life in a world long past.

Intriguingly, it was amidst the #archaeological excavations of the 19th Dynasty settlement that this limestone tablet saw the light of day once again. Carefully unearthed from the layers of history, the ostracon emerged as a silent sentinel of antiquity, carrying with it the echoes of voices that toiled and triumphed over three millennia ago. The journey from its moment of creation, during reign of Ramses II around 1250 BC, to its rediscovery, offers a tangible connection to the aspirations, struggles, and dynamics of a workforce whose endeavors shaped the very foundations of ancient civilization.

📷 : A limestone ostracon, listing workers and their reasons for being absent on certain debates, mark dLabelled ‘Year 40' of Ramses II, 1250 BC. (📷© The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

archaeology Histories News on Umojja.com