View 465 times

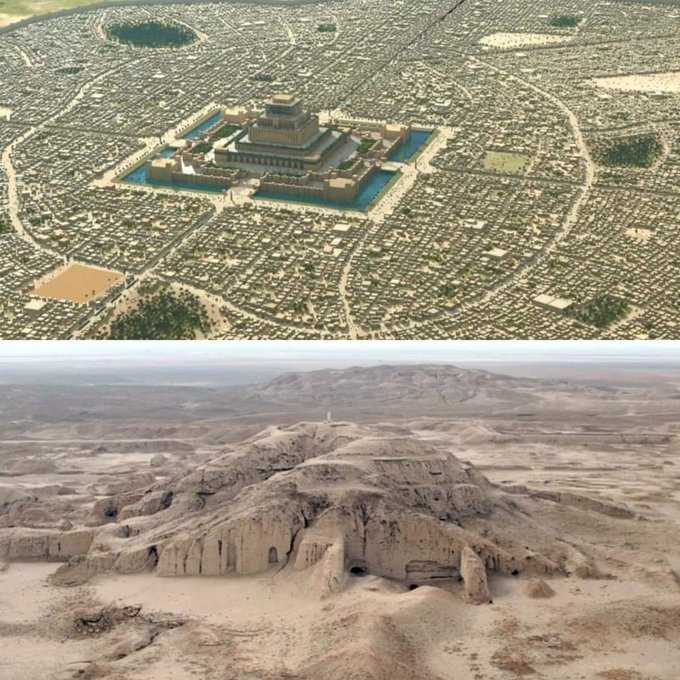

Uruk - the initial city of human civilization that changed the world with its advanced knowledge :

The cuneiform tablets discovered at Nineveh include fascinating information about giants, weird beasts, and enigmatic flying ships.

Of all these, most striking is that of Gilgamesh, considered oldest epic of mankind. A 5000 years ago, he ruled Uruk despotically, and that certain historical texts show him as someone who really existed, but with a fantastic and unknown origin. Unfortunately, its complete history has not survived over time, but what can be perceived in the rest of the tablets found, shows a history of struggle, life and death. Sumerians considered Gilgamesh to be “the man (entity or being) for whom all things were known (unlimited knowledge)”. They said it was a hybrid between gods “who came from heaven” and humans.

Uruk continues to hold many human mysteries, shocking traditional archaeology with each new dig with stories that have been concealed from us for decades. Uruk is a clear example of this, along with his stories about gods that make us wonder if there really was no “influence” beyond what we know.

Uruk was a city that flourished south of the river valley, on the banks of the Euphrates, and its civilization expanded throughout Mesopotamia to become the world’s earliest and most significant metropolis. Cradle of mythical rulers such as Gilgamesh.

A God who was far far from what we recognise as “human” and more akin to a mystery creature. But, before we get to Gilgamesh, we must first discuss the beginnings of one of antiquity’s most mysterious civilizations. It was discovered in 1849 thanks to William Loftus, despite the fact that the most renowned archaeologists did not reach it until the following century; 1912-1913. Julius Jordan together with the East German Society discovered the Ishtar temple at that time, surprising it with its adobe mosaics and bricks. But what surprised him most were the ruins of the ancient wall that covered the entire city for more than 3,000 years BC, which, according to later studies, reached more than 15 meters in height and was more than 9 kilometers long wall built by King Gilgamesh.

In 1950s, Heinrich Lenzen found some tablets written in Sumerian dialect and dated 3300 BC and that described Uruk as first urban center that used writing as a common means of communication in everyday life. All of these discoveries demonstrated, quite contrary to what everyone believed at the time, that Uruk became, not only first urban human settlement, but also nucleus of society, with a flourishing economic power superior to anyone. In addition, it stands out in the succession of temples crowned in ziggurats and palaces, at least 80,000 inhabitants, making it the first city on the planet.

Throughout its history, Uruk has also lived through different stages, its foundation being a Neolithic settlement around 5000 BC, making it a powerful city, significantly advanced and considerably influential between 4000-3000 BC, until its fall after 700 AD. Even so, Uruk’s influence was so powerful, that it takes a period of time to bear his name, making it most influential metropolis of human societies. However, it is not yet known how Uruk came to be the epicenter of society and had so much dominance. His economic power was known, the perfect lands that existed in the valley of the two rivers, which certainly made him grow the best food in the region.

Possibly this attracted more people who joined urban planning, creating business with different regions, making people not need to fight for their livelihood, giving them the opportunity to dedicate themselves other tasks, creating all kinds. But it is also believed in theoretical circles (theorists of ancient astronauts, alternative theorists and others who do not believe in history as we were told) that he had a “divine” influence, which did not belong to this planet.

View 445 times

Do even the Gods bow to Abrahamic norms now or something else ?

Jalanetheshvar Temple, Tamil Nadu

C. 800 CE

#Archaeology questions

View 293 times

Temple of Hephaestus, 5th c. BC

Ancient agora of Athens

View 292 times

archaeology Histories News on Umojja.com