Researchers spot rare evidence of how two baby #pterosaurs died 150 million years ago.

A violent storm may have sent two baby pterosaurs spiraling to their deaths in a lagoon about 150 million years ago, based on a new analysis of the tiny, astonishingly well-preserved fossils. This latest research also provides fresh clues that may unravel a broader enduring mystery surrounding the site where the specimens were found.

The prehistoric flying reptiles, nicknamed Lucky and Lucky II by the authors of a new study published in the journal Current Biology on September 5, were likely a few days to weeks old when they died in what is now southern Germany.

The fossils, which dated to between 153 million and 148 million years ago during the Jurassic Period, are among the smallest pterosaur specimens ever found, with wingspans of less than 8 inches (20 centimetres). Small bones don’t often preserve well in the fossil record because they break so easily — especially ones as delicate as lightweight, hollow pterosaur bones.

At first glance, the skeletons appear pristine, seemingly representing how the pterosaurs would have appeared when they were alive. But each one bears a similar injury. Lucky’s left upper arm bone, or humerus, and Lucky II’s right upper arm bone both show a clean, slanted fracture, suggesting they were twisted by powerful wind gusts.

The researchers believe that after sustaining their injuries, the pterosaurs fell into the lagoon and drowned in the waves, falling to the seabed where mud stirred up by the storm rapidly buried them. Ironically, the very storm responsible for their deaths is likely what preserved their skeletons so well, the researchers said.

“The odds of preserving (a pterosaur) are already slim and finding a fossil that tells you how the animal died is even rarer,” said lead study author Rab Smyth, a paleontology researcher at the American Museum of Natural History, in a statement. Smyth conducted the research as a doctoral student at the University of Leicester’s Centre for Palaeobiology and Biosphere Evolution in the United Kingdom.

In addition to shedding light on how the pterosaurs died, the fossils may reveal why researchers have uncovered the remains of hundreds of small pterosaurs, but few large ones, within the Solnhofen Limestone of southern Germany.

Islands of discovery

About 150 million years ago, Europe looked completely different, Smyth said.

“The continent was broken into a complex chain of small islands,” he wrote in an email. “Southern Germany, among the last specks of land before the vast Tethys Ocean stretching toward Africa, consisted of semi-arid islands covered in low, shrub-like vegetation.”

The Solnhofen lagoons were part of an archipelago, with the nearest landmasses just a few miles away, he said.

Researchers have regularly recovered well-preserved small pterosaur fossils for the past 240 years from the lagoon deposits at Solnhofen, Smyth said. In contrast, scientists have found only fragments, such as skulls or limbs, of larger adult pterosaurs. The lack of complete adult specimens is unusual because larger animals tend to fossilize better, the researchers said.

The fossils recovered from the Solnhofen Limestone, including 500 specimens representing 15 different species, have “long underpinned and continues to dominate much of our understanding of these flying reptiles,” the authors wrote in the study.

Knowledge of just how the specimens became fossilized in the region has remained limited.

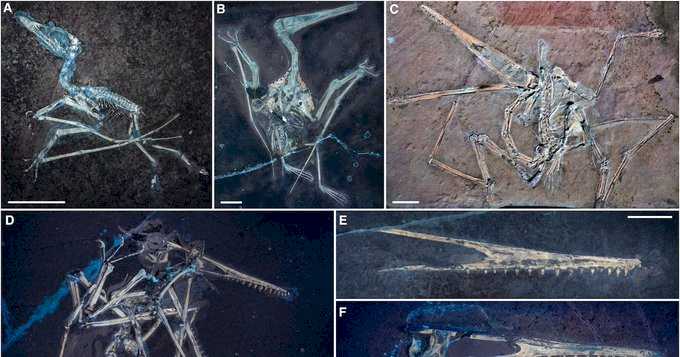

Smyth and his colleagues studied the two fossils, held at the Museum Bergér in Harthof and the Bavarian State Collection for Palaeontology and Geology in Munich, using Ultraviolet Fluorescence Photography, to search for clues.

The technique revealed details difficult to see in visible light alone, like areas of soft tissue preservation, the condition of the limestone in which the fossils were preserved, and the thickness of the hollow walls of the bones. The fossils are also distinctive in that they show evidence of bone trauma, unlike the other small pterosaur remains found in Solnhofen.

“When Rab spotted Lucky we were very excited but realised that it was a one-off,” said study coauthor Dr. David Unwin, reader in paleobiology in the School of Museum Studies at the University of Leicester, in a statement. “A year later, when Rab noticed Lucky II we knew that it was no longer a freak find but evidence of how these animals were dying. Later still, when we had a chance to light-up Lucky II with our UV torches, it literally leapt out of the rock at us — and our hearts stopped. Neither of us will ever forget that moment.”

Some of the fossils found in the limestone belong to the pterosaur species Rhamphorhynchus muensteri and Pterodactylus antiquus, and both Lucky specimens belong to the latter. But the researchers thought it was unusual to find hatchling and juvenile P. antiquus within the lagoon, since the species didn’t appear to have any adaptations for a marine lifestyle.

Rhamphorhynchus muensteri, on the other hand, had long, gull-like wings and jaws suited for catching fish and squid. There are also many examples of specimens ranging from young to adult pterosaurs, as expected of a local population, Smyth said.

Instead, Smyth believes the Lucky pterosaurs and other juvenile Pterodactylus antiquus specimens lived on the landmasses near the lagoons.

“These islands and coastal areas were likely semi-arid, with sparse forest or scrub,” Smyth said. “They supported a variety of invertebrates and small reptiles, as well as Archaeopteryx, one of the earliest known birds. We know this because these plants and animals are occasionally found washed into the lagoons.”

Researchers are still recovering a variety of pterosaur specimens from the Solnhofen Limestone, allowing scientists to study pterosaur growth, variation and anatomy in much greater detail, Smyth said.

A lucky find

Studying the Lucky pterosaurs helped the researchers realize how prehistoric tropical storms led to a bias in the fossil record.

Much of the time, the lagoons would have been calm, with shallow waters. But they were ticking time bombs, Smyth said. The water column contained specific layers, with an oxygenated surface above a super-salty, oxygen-free bottom.

“Sudden storms could churn the lagoon, bringing the toxic bottom water to the surface and causing mass die-offs of marine life,” Smyth said. “At the same time, the storms could sweep other animals into the lagoons, including young pterosaurs, which were quickly buried in fine sediment.”

The fact that so many of the young pterosaur fossils are so complete suggests they were buried shortly after the storms occurred before scavengers could disturb them, he said.

But how did nonlocal pterosaurs end up in the lagoon? The young hatchlings were likely unable to escape the strong stormy winds, unlike adult pterosaurs.

“For centuries, scientists believed that the Solnhofen lagoon ecosystems were dominated by small pterosaurs,” Smyth said. “But we now know this view is deeply biased. Many of these pterosaurs weren’t native to the lagoon at all. Most are inexperienced juveniles that were likely living on nearby islands that were unfortunately caught up in powerful storms.”

Meanwhile, adult pterosaurs, better able to withstand the storms, likely died of natural causes and floated for days or weeks on the lagoon surface, with pieces of their remains slowly falling to the bottom.

Flight of the baby pterosaurs

Now, Smyth and his colleagues want to better understand how hatchling pterosaurs were able to fly so early in life, which is something almost no modern flying animal can do, he said.

Scientists have previously debated the flying capabilities of baby pterosaurs, but the study suggests that the Lucky pterosaurs sustained flight-related injuries similar to those seen in birds, especially inexperienced juveniles that fly through marine storms, the authors wrote in the study.

David Martill, professor emeritus at the Institute of the Earth and Environment at the University of Portsmouth, was fascinated by the study and UV images. Martill did not participate in the research and has some reservations about the injuries having been caused by storms. The injuries tend to occur when animals are bashed against rocks, and there were no cliffs present in the lagoons, he suggested.

“So, I welcome this study as an extremely interesting hypothesis that requires deeper study,” Martill wrote in an email.

Steve Brusatte, a professor of paleontology and evolution at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland who was also not involved in the research, called the study “paleontological detective work of the highest caliber,” providing rare evidence of how animals died and fossilized.

“When you think about it, each fossil is a tragedy,” Brusatte wrote in an email. “It’s part of a plant or animal that has died and gotten buried and turned into rock. This study is a haunting window into the lives of pterodactyls. I can actually envision in my head, a dark and stormy night in the Jurassic, when the winds of fate took down these pterodactyls, turning them into the fossils that we celebrate 150 million years later.”

By Ashley Strickland, CNN

archaeology Histories News on Umojja.com