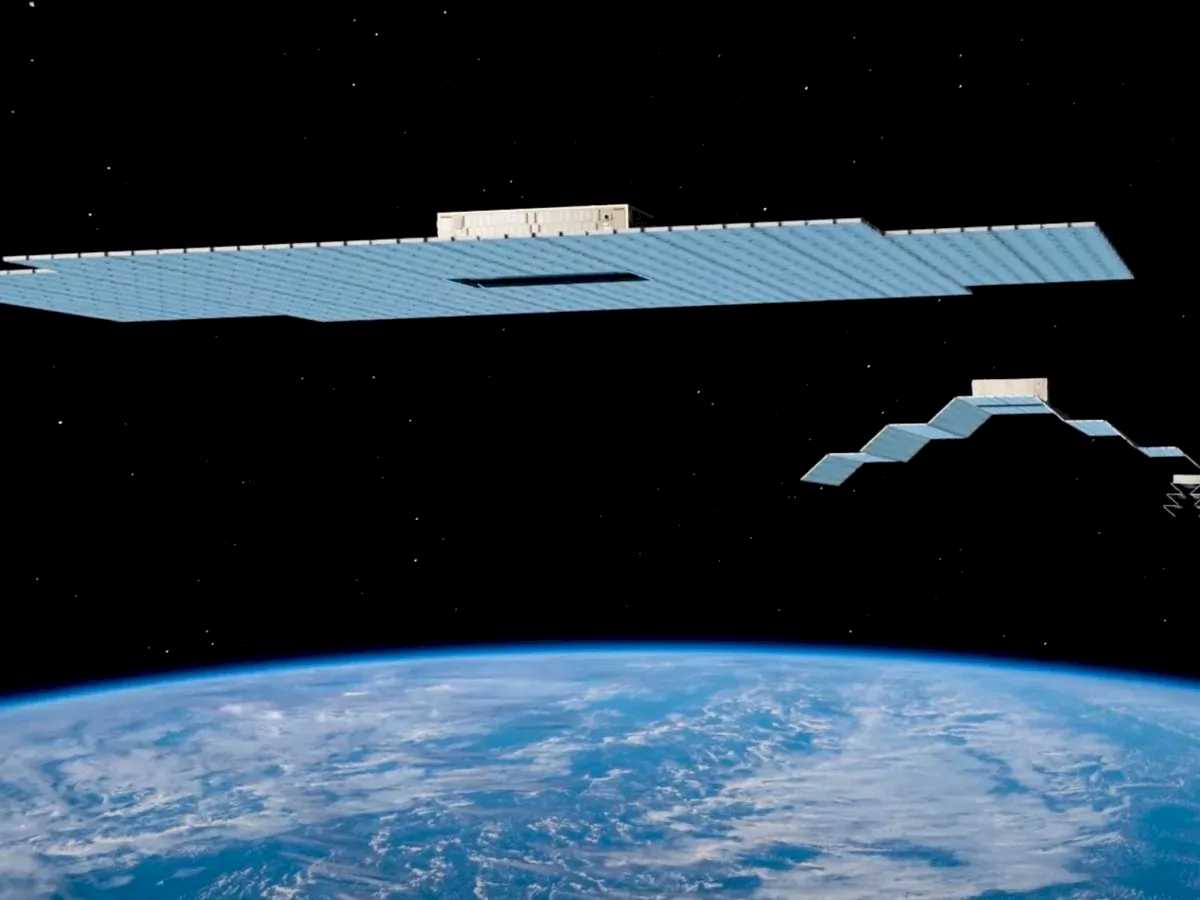

WASHINGTON — A startup plans to test technology to produce semiconductors in space on a series of Falcon 9 launches using payloads attached to the rocket’s booster.

Besxar announced Oct. 28 it signed a launch agreement with SpaceX to fly payloads on 12 Falcon 9 missions that could begin before the end of the year. The companies did not disclose terms of the agreement.

Unlike typical Falcon 9 customers, Besxar will not place payloads into orbit. Instead, each of the 12 launches will carry two “Fabship” payloads attached to the boosters, which will return to Earth with the boosters when they land less than 10 minutes after liftoff.

The payloads, each about the size of a microwave oven, are designed to test systems Besxar is developing to produce semiconductor wafers in the vacuum of space.

“I’d like to believe we’re taking a bit of a different approach,” Ashley Pilipiszyn, Besxar’s founder and chief executive, said in an interview. “One of the things that we realized is companies like SpaceX have figured out launch and reentry really well and on a repeatable basis.”.

Those initial Fabships, which the company calls “Clipper-class” payloads, are primarily intended to test whether semiconductor materials can safely launch and land.

“This is pretty much the ultimate egg drop challenge,” she said. “We wanted to ensure that not only could we get wafers to and from space and do all these wonderful things with them and do deposition, but can we actually reliably bring them back without warpage, cracking, anything like that.”

Booking a dozen flights, Pilipiszyn said, enables the company to rapidly iterate on the Fabship design, including reusing hardware. She compared the Clipper-class payloads to SpaceX’s “hopper” prototype for Starship, which tested takeoff and landing technologies.

“That is really, I think, a different way of thinking about the space economy,” she said. “It’s not just price per kilogram, it’s how many times you’re launching and what your turnaround time is.”

The 12 missions are expected to take place over the next year. Pilipiszyn said she expects the company to learn enough from the series to move into a new phase of missions but did not disclose details.

While many space manufacturing ventures aim to exploit microgravity, Besxar is focused instead on vacuum conditions. That, she said, could enable the purity required for semiconductor fabrication without the enormous expense of recreating such conditions on Earth.

Pilipiszyn noted that semiconductor manufacturer TSMC plans to spend $50 billion on a new fabrication plant for advanced chips. Much of that cost, she said, comes from the equipment and processes needed to maintain ultra-clean environments, something that space could provide naturally.

“The vacuum of space is really key for us,” she said. “Microgravity is a benefit. It’s not like it does anything negative, but it’s not the core offering.”

Besxar, based in Washington, D.C., has “more missions on contract than employees,” Pilipiszyn said. The company has raised an undisclosed amount from “strategic angel” investors as well as institutional backers. That funding, she said, is enough to complete the Clipper-class series of missions on SpaceX launches.

“We view ourselves as an American semiconductor manufacturing company that happens to work in space, versus a space company as we typically think about them,” she said. Besxar’s goal, she added, is to use space to improve semiconductor manufacturing and keep the U.S. competitive with #China.

“One of the things we’re really striving to champion is that in-space manufacturing is American manufacturing and really just part of this larger supply chain,” she said.

Space news on Umojja.com